|

Abbreviated CV

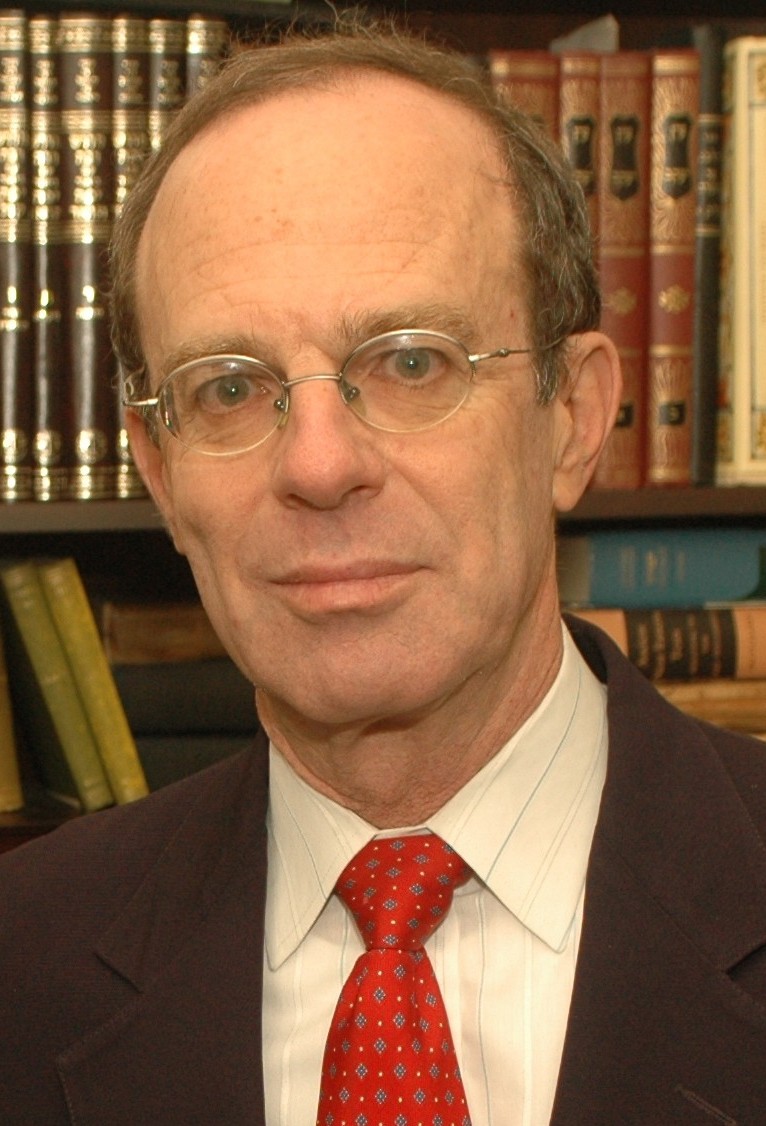

As of July 1, 2006, Marc Saperstein goes on extended leave from GWU to assume the position of Principal of the, Leo Baeck College-Center for Jewish Education in London. He has held the position of Charles E. Smith Professor of Jewish History and Director of the Program in Judaic Studies at the George Washington University since July 1997. Previously, beginning in 1986, he held the newly established Gloria M. Goldstein Chair in Jewish History and Thought at Washington University. He served as Chairman of its Program in Jewish and Near Eastern Studies from 1989-1997.Professor Saperstein received a BA summa cum laude at Harvard, an MA at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, rabbinical ordination at the New York School of Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion, and a Ph.D. at Harvard. He taught on the Harvard faculty for nine years, holding the first regular faculty position in Jewish Studies at Harvard Divinity School; he has been visiting professor at Columbia University, University of Pennsylvania, and the Revel Graduate School of Yeshiva University.

He is the author of five books, Decoding the Rabbis (Harvard University Press, 1980), the widely acclaimed Moments of Crisis in Jewish-Christian Relations (SCM-Trinity Press International, 1989), Jewish Preaching 1200-1800 (Yale University Press,1989), which won the National Jewish Book Award in the area of Jewish thought, and "Your Voice Like a Ram's Horn" (HUC Press, 1996), also granted a National Jewish Book Award. His latest book, Exile in Amsterdam, was published by the Hebrew Union College Press in 2005 and received an honorable mention for a National Jewish Book Award. The editor of Essential Papers on Messianic Movements and Personalities in Jewish History and Witness from the Pulpit, he has also written 60 articles and more than 30 book reviews on various aspects of Jewish history, literature, and thought.

Dr. Saperstein has been awarded the Henry Fellowship, the Kent Fellowship, an American Council of Learned Societies Research grant, and research fellowships at the Institute for Advanced Studies of the Hebrew University, the Center for Judaic Studies at the University of Pennsylvania, and the Center for Jewish Studies at Harvard University. During a fall 2002 sabbatical leave, he was the Rabbi Hugo Gryn Visiting Fellow in Religious Tolerance at the Center for Jewish-Christian Relations in Cambridge, England. He was Book Review Editor for the Association of Jewish Studies Review from 1997 to 2002 and was a a member of the AJS Board of Directors from 1983 to 1999. In 1994, he was elected to be a fellow of the prestigious American Academy for Jewish Research. He served as Treasurer of the Academy from 2000 to 2004 and Vice President from 2002 to 2006.

Back to Top

Books

- Decoding the Rabbis: A Thirteenth-Century Commentary on the Aggadah

- Jewish Preaching, 1200-1800

- Moments of Crisis in Jewish-Christian Relations

- "Your Voice Like a Ram's Horn:" Themes and Texts in Traditional Jewish Preaching

- Witness from the Pulpit: Topical Sermons, 1933-1980

- Exile in Amsterdam: Saul Levi Morteira's Sermons to a Congregation of New Jews

Decoding the Rabbis: A

Thirteenth-Century Commentary on the Aggadah

Harvard University Press, 1980

From the Preface:

This book is about the work of a thirteenth-century Provencal author named R. Isaac ben Yedaiah. The reader who turns to any of the standard reference books for background information about R. Isaac will be disappointed. No one of such a name is to be found in the Jewish encyclopedias or in the general histories of Hebrew literature or even in the monumental bibliographic studies of the Wissenschaft des Judentums. I am suggesting that a new figure in the history of Jewish culture has been discovered, the importance of whose work is by no means belied by the fact that his traces were all but lost in subsequent Hebrew literature.

If one purpose of this book is to reclaim an individual author, the second major purpose is to delineate upon the broad canvas of Jewish cultural history the area of his major interest and efforts. The history of interpretation of the aggadah has yet to be generally recognized as a subject worthy of systematic study. While many scholars have begun to apply various analytical tools to the aggadah itself, there has been relatively little investigation of the ways in which Jews throughout the ages have interpreted the aggadah in response to changing intellectual assumptions, new historical pressures, the intrinsic challenge of the material itself, and the demands of an educated community for novel insights into familiar texts. Many of the most important works of aggadic exegesis remain in manuscript; these must be published and studied before any general survey-even for a single geographical area such as southern France-may be safely attempted. I hope that my monograph will demonstrate the importance of this exegetical genre, not so much for the insights it may bring into the original meaning of the Talmudic material as for the light it throws upon the medieval Jewish mind, drawing upon an ancient and venerable literature to contend with the challenges of new intellectual movements, the lures of powerful daughter religions, the agonies of external oppression and inner social strife. This study of Isaac ben Yedaiah's commentaries is, therefore, not a work of pure history or philosophy or literature. It is rather an attempt to follow two major documents, one of them hitherto unknown, wherever the texts themselves lead and to extract from these documents their full significance for our understanding of the Jew and his culture in medieval Europe.

Back to Top

Jewish Preaching, 1200-1800

Yale University Press, 1989

*Winner of the 1990 National Jewish Book Award in the category of Jewish Thought given by the Jewish Book Council.

"A scholarly masterpiece and an intellectual tour de force that

must be read by anybody with a serious interest in Jewish studies or the art of

preaching."

--Howard Adelman, Shofar

"This splendid and interesting collection, a description true of

all the Yale Judaica, is richly documented."

--Thomas L. Shaffer, Christian Legal Society Quarterly

"A work of profound scholarship, it is also a pleasure to

read."

--Choice

"A groundbreaking work of exquisite scholarship that truly points

the way for others to follow."

--David E. Fass, American Rabbi

"Jewish Preaching offers the reader an exceptional

overview of many different and fascinating aspects of Jewish history, culture, and

theology."

--Yaakov Ort, Wellsprings

"Saperstein's careful and detailed translations and annotations,

and his cogent introductory essay, are examples of scholarship at its highest level, and

should serve to secure the place of this body of literature in the field of Jewish

studies."

--from the citation for the Present Tense/ Joel H. Cavior Literary Award, 1990

From the Preface:

This book has been written with several different audiences in mind. For academic colleagues in the various fields of Jewish studies, my work constitutes a special plea to reclaim a neglected area of Jewish creativity through further investigation. Much of the scholarly apparatus, including references to comparative material in manuscripts or in early printed books, and indications of relevant comparisons in studies of Christian preaching, is intended primarily for them.

For the many scholars devoted to research on various aspects of Christian preaching, especially the members of the Medieval Sermon Society, whose Newsletter and symposia have been a rich resource for me, I have attempted to render accessible a body of material in which they have evinced a keen interest. The full extent of interaction between Jewish and Christian preaching during the period I treat remains to be explored, but I believe that interaction in our respective fields of research today will yield mutually illuminating results.

For colleagues in the active rabbinate, preaching is an ongoing responsibility and challenge. The material in this book is not primarily intended to suggest model sermons or even homiletical ideas for contemporary use, but rather to foster an appreciation of the preaching tradition that contemporary rabbis represent by demonstrating how predecessors molded sacred texts to address the intellectual, social, and spiritual problems of their own time.

For college-level students of Jewish life and thought in the Middle Ages and in early modern times, this book is meant to provide an introduction to the central intellectual issues, spiritual movements, and communal centers during six critical centuries of Jewish experience. For their benefit, I have referred wherever possible to scholarly works available in English translation and to readily accessible editions, rather than to rare first editions of Hebrew primary texts.

Finally, for readers who are analogous in our own terms to the congregations for whom the sermons were originally intended, the following material can enhance an understanding of their counterparts, fostering insight into the level of education, the problems, concerns, and a aspirations of the ordinary Jew. For the sermon perhaps more than for any other genre of literature, the presence of an audience is critical, and the nature of this audience must never be overlooked.

Back to Top

Moments

of Crisis in Jewish-Christian Relations

SCM-Trinity Press International, 1989

"The moments of crisis in Jewish-Christian relations, which Marc

Saperstein has distilled from the long and mostly painful history and from his own rich

research and teaching, are at the same time those that can educate habits of mind and

heart toward greater wisdom. Here is a good help to change our ways of thinking. Here is

an ideal book for study groups and courses among Christians or, even better, in dialogue

between Jews and Christians"

--Krister Stendahl, Harvard Divinity School and Bishop of Stockholm, Emeritus

"Provides an ongoing agenda for this new era in our common history.

This volume belongs on every college and seminary Western-history-course syllabus."

--Journal of Ecumenical Studies

From the Preface:

Throughout my presentation, I have aspired toward the historian's goal of detachment. Drawing from the best available scholarly research, I have attempted not to advocate, judge or condemn, but rather to reconstruct the range of options facing individuals in their own historical contexts, to explain insofar as possible the reasons for the choices that were made, and to assess the implications of such decisions for subsequent developments. I recognize, however, that the ideal of objectivity in historical writing is illusionary, for fundamental decisions about the selection and organization of one's material necessarily entail value judgements. The historian's position is particularly precarious in moving, as I have done in my final chapter, from the past to the present. It is therefore appropriate to articulate my own commitments and the preconceptions that may inform the material to follow.

I am a rabbi in the liberal, Reform branch of Judaism, and an academic trained in the critical analysis of historical sources. I am committed to the survival and flourishing of the Jewish people both in the Diaspora and its ancestral homeland, though I do not consider myself to be a spokesman for any political position or to use historical arguments for any ideological goal. I reject the notion, found occasionally in traditional Jewish literature, that conflict and enmity are the natural paradigm for the relationship between Jews and Gentiles. I believe that a full and balanced confrontation with the record of the past in all its horrors is a necessary precondition for honest and open relations in the present, yet I also believe that those living today bear no responsibility for the misdeeds of their ancestors, and that guilt cannot serve as a solid foundation for any healthy relationship.

I am deeply concerned about the resurgence of fundamentalist, fanatical, extremist views not only within Islam and Christianity but also within contemporary Judaism, often justified by appeals to Jewish texts and claims to be the only "authentic" Judaism. These claims seem to me to be ethically barren, politically dangerous, and intellectually dishonest. I am impressed by the diversity of sources in both the Jewish and the Christian traditions, each containing elements of a universalistic openness toward the Other, and also of suspicion and hostility which sees all good within one's own camp, and outside that camp at best nothing of value and at worst the forces of the demonic. Neither one of these strands has a clear prima facie claim for authenticity; which one is emphasized and expressed at any historical juncture is, for better or for worse, the result of the decisions of human beings, who may believe that they are acting in accordance with God's will, but who may very well be mistaken. My understanding of the historical record described below is that it demonstrates the capacity of decent, sincere, religious people for cruelty, stupidity, and callous indifference to the suffering others, but also for sacrificial devotion to the most ennobling of values.

Back to Top

"Your Voice Like a Ram's

Horn:"

Themes and Texts in Traditional Jewish Preaching

Hebrew Union College Press, 1996

*Awarded National Jewish Book Award

From the Preface:

Several underlying principles characterize my approach to the history of Jewish preaching in these studies. The starting point is the text of the individual sermon. There can be no substitute for the painstaking effort to identify those texts, whether in manuscript or print, that reflect the core preaching event: the oral communication, usually within the context of a public religious ceremony, in which a speaker expounds the meaning of classical Jewish texts in a manner intended to address the intellectual or spiritual needs of the listeners. The attempt to locate, identify and present such texts in accordance with the standards of modern scholarship has been a major preoccupation of my research.

The present book reveals three ways in which I try to situate these texts within a broader framework. The first is the immediate context: What was the situation in which the preacher and the listeners came to the sermon? What were the problems being addressed? What resonance would allusions within the sermon have had for a contemporary audience that may well be lost on us? Second is the broader contemporary context: How does this text relate to issues and concerns expressed in other sermons by the same preacher, or by other preachers-Jewish or Christian-in the same community or the same region, at roughly the same time? Third is the diachronic element: How does this text fit into the centuries-old tradition of Jewish preaching? What elements of the sermon are conventions and topoi? And where is the preacher consciously modifying, or departing from, such conventions? The studies in Part One focus more on the second and third dimensions; those in Part Two, more on the first. But all of these questions must inform any responsible analysis.

Back to Top

Witness

from the Pulpit: Topical Sermons, 1933-1980

Harold I. Saperstein

Edited with Introductions and Notes by Marc Saperstein

Lexington Books, January 2000

From the Introduction:

The following sermons were selected from a repository of some 800 extant typescripts, written for delivery by my father, Rabbi Harold I. Saperstein, in an active rabbinic career of some sixty years, beginning in 1933. Some words about the criteria for selection are therefore necessary.

I decided, first, to make the cut-off date 1980, the year he retired as rabbi of Temple Emanu-El of Lynbrook. He had served this one congregation for forty-seven years, during which it grew from some eighty families when he arrived in 1933 to a peak of about 1,000 families. One of the salient characteristics of the material is that it reveals a rabbi speaking to the same congregation over a period of almost two generations. There are a few exceptions. The first sermon, from the spring of 1933, dates from before he went to Lynbrook. The Rosh Hashanah sermons of 1944 and 1945 were delivered in Europe while he was a chaplain with the American Army. There is an address at a 1970 rally protesting the verdicts in the "Leningrad Trials," given while he was President of the New York Board of Rabbis. There is a sermon to the convention of the Central Conference of American Rabbis in 1957 and a sermon at ordination ceremonies of the Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion in 1972. Except for these, all of the sermons in this book were delivered in the Lynbrook Temple.

I will return to the implications of this factor for a preacher later. Here I want to emphasize that remaining in one suburban congregation for forty-seven years did not in this case imply a narrow range of experience. The specific contours of Saperstein's career-as a young rabbi close to Stephen S. Wise near the dynamic center of American Jewish issues; a visitor to Palestine, Poland, and a delegate to the Geneva World Zionist Congress while the clouds of war were gathering in the summer of 1939; a chaplain in the European Theater during the war, entering Dachau with American forces days after its liberation, helping survivors in France, Germany, and Belgium; one of the early rabbis to visit and speak out publicly about Soviet Jewry after visits in 1959 and 1961; a volunteer working on voter registration with Stokely Carmichael in Lowndes County, Alabama during the turbulent summer of 1965; a resident of the Hebrew Union College bordering no-man's land in Jerusalem during the Six-Day War; President of the New York Board of Rabbis at the time of the Leningrad Trials verdict, on the cutting edge of confrontation with the Jewish Defense League; an inveterate, almost compulsive traveler who, with his wife, Marcia, visited Jewish communities in more than eighty countries on six continents-seem to reflect a sustained effort to be "where the action is," and to use the pulpit of his suburban Temple to report on personal encounters with great issues of the day.

Because of the nature of this rabbinic career and my own interests in the academic study of Jewish sermons, I set as my goal to find among some 800 extant typescripts topical sermons, which addressed specific issues of the day. Most homiletical collections tend to avoid the topical sermon, for a simple and obvious reason. What may have seemed an urgent, pressing, burning issue at the time of delivery looks very different ten, twenty, forty years later. Frequently it will have diminished into a historical footnote. The precise questions that once loomed so large are all but forgotten with the passage of time. References and allusions to then current matters of discussion seem almost opaque. What was once a front-page headline now seems dated and trivial. "Who will care about this anymore?" one thinks. Furthermore, subsequent years often reveal that prognostications made with confidence by the preacher have turned out to be totally misguided, and positions held with deep conviction but later abandoned may appear somewhat embarrassing. There is thus a natural tendency to prefer for publication the "timeless" sermon, homiletical in nature, textual in orientation, the kind of material that will speak to people as directly today as when first delivered a generation ago.

Especially for other clergy, there are undeniable attractions to the "timeless" sermon that can be delivered, or heard, with undiminished impact twenty years after its original creation. As a historian, however, my interest in past sermons is different. For me, the most fascinating texts are the ones that bring us back to a unique moment in the past and allow us to recover the complex dynamics, the agonizing dilemmas, the deep passions of a point in time that seems ever more elusive. Such are the sermons I have chosen for inclusion in this book, trying to find, on the average, one for every year from 1933 through the 1970s. Cumulatively, they portray the hopes and fears, the triumphs and failures, of a rabbi and a suburban congregation from the Reform movement, representing a significant component of the American Jewish community, over the course of two generations. To say that these were turbulent times seems almost trite. Nazism and the Holocaust; Zionism, the birth of the State of Israel and its subsequent ordeals and triumphs; the withering and revivification of Soviet Jewry; the Civil Rights Movement and the Vietnam War; the assassinations of President Kennedy and the Rev. Martin Luther King-these were not trivial events that could be easily ignored. What were rabbis saying at these times? What were Jews in their congregations hearing?

One example will illustrate. Having taught an undergraduate course on the Holocaust for more than ten years during a period when my academic research focused on medieval and early modern Jewish preaching, I was fairly certain about the value of sermons for determining what was known and thought during the Holocaust era. Memoirs, for all their importance and inspiration, are problematic as historical sources because of the natural tendency to reconstruct the past by projecting backward what was known only at a later time. Contemporary, datable sources are obviously preferable in this respect. Diaries are invaluable, but they are by nature private documents; they reflect the views of the author, but how do we know how well they represent anyone else? Considerable study of late has been focused on newspapers and periodicals of the period. This has demonstrated what information was available, accessible; it does not show what people actually read, heard, internalized and absorbed.

The sermon addressed to a congregation arguably takes us beyond the newspaper, especially since much of the most important information about the murder of European Jews tended to be buried on inside pages. Obviously, not every member in the congregation attends services, not everyone seated in the pews listens or hears; some people tune out or fall asleep even when the best preachers are speaking. Nevertheless, a case can be made that when a rabbi delivers a message during a worship service, especially on the Days of Awe, when Jews tend to be in a more than usually receptive mood, the evidence of actual communication about matters of utmost urgency is especially pertinent.

What was being said about Nazism to an average New York suburban congregation of Reform Jews? Was the danger of the Hitler regime to German Jews recognized? What was being urged about the economic boycott of Nazi Germany? About American participation in the Olympic Games? How much was communicated from the pulpit about the actual murder of Jews during the war itself? What was the mood of rabbis and congregants as news about European Jewry-and Europe itself-became worse and worse, and what homiletical efforts were made to lift that mood? What did rabbis advocate about America's role between the beginning of the war on September 1, 1939 and December 7, 1941? Is it true that American Jewish leaders "remained silent," "did nothing," were guilty of indifference, afraid of confrontational protest? Is it fair to state that "the destruction of the Jew of Europe was all but ignored when it was happening"? (New York Times, August 8, 1998, A17). I am not aware of any study of such questions based on sermons delivered between 1933 and 1946. The texts published below will provide the foundation for some preliminary answers.

Back to Top

Exile in Amsterdam: Saul Levi

Morteira's

Sermons to a Congregation of "New Jews"

Hebrew Union College Press, 2004

From the Epilogue:

Concluding this survey of the records of Morteira’s homiletical output, it seems appropriate to summarize its content and significance. I begin with what is missing, what I have not discovered in these texts. Some modern preachers regularly introduce themselves into their sermons, using their own experiences, spiritual struggles, intellectual perplexities and triumphs, whether recent or early in their lives, as a basis for the message directed to others. Like most pre-20th century Jewish preachers, Morteira rarely speaks about himself. Occasionally, especially in the eulogies, he will mention his own relationship with the deceased. Sometimes he will talk about his difficulties in deriving an appropriate message from the Biblical verse at hand. If the sermon was delivered in conjunction with a life cycle event of a family member (e.g. the betrothal or wedding of one of his daughters), this will be noted at the end. The first-person singular pronoun appears when he is referring the listeners to a sermon he delivered in the past, or a book he has read, a conversation with a Christian thinker, or an interpretation by his distinguished grandfather (Judah Katzenellenbogen) or his mentor Elijah Montalto. But the personal voice of the preacher is difficult to detect in these texts. One reads through hundreds of pages without learning anything about his biography (his parents and siblings, childhood, his education in Venice or the years spent with Montalto in France), or even his personality. For this we need the archival records of the Amsterdam community. The sermons reveal his mind and his aesthetic sense, not his life or his emotions.

Many names from the community appear in the texts, especially in the postscripts that provide information about the circumstances of delivery. These details complement the archival records about individuals and institutions. Several of the eulogies poignantly illuminate personal qualities and experiences of such important community figures as Abraham and Sarah Farar and David their son, as well as David Masiah and Rabbi Menasseh ben Israel. But we look in vain for explicit mention of the most famous "heretics" of the time: Uriel da Costa, Juan de Prado, Barukh Spinoza. I have found no mention of the Venetian rabbi assumed to be Morteira’s primary teacher, Leon Modena>no reference to a personal relationship, no citation of Modena’s works>or of Morteira’s colleague in Amsterdam and Recife, Isaac Aboab da Fonseca, with whom he engaged in a vehement intellectual polemic over the ultimate punishment for unrepentant sinners. While he refers occasionally to “the books of the Gentiles,” he does not appear to cite by name any Christian thinker. Where exempla are introduced for a homiletical purpose, they are of nameless types (a nursing mother, a person attempting to study alchemy, a printer, a master artist and his school of disciples), not of real individuals.

If we did not know where Morteira was delivering the sermons, it would be difficult to identify the unique environment of Amsterdam from internal evidence. The one dramatic survey of the discrimination and oppression suffered by Jews in the other great contemporary communities, and a reference to the absence of any requirement for distinctive clothing would be the best clues. But the sermons appear to contain no explicit reflection on the civic government of Amsterdam (or of his native city, Venice); the various discussions of political theory in the texts seem to be based on the monarchy of the Biblical sources. While Morteira speaks about the uncertainties of wealth, I have found no reference to the celebrated tulip craze of 1636-1637. I have found no reference to the princes of the House of Orange who reigned during Morteira’s tenure; no specific mention of (though a probable allusion to) the lapse of the Twelve-Years Truce with Spain in 1621; no reference to the Thirty Years War or the dramatic Treaty of M|nster that ended it in 1648, or to the Anglo-Dutch War of 1652-54. While Morteira uses history>mainly ancient history>for homiletical purposes, with rare exceptions these sermons are not texts from which to learn about contemporary events. Nor is there evidence of intellectual confrontation with the challenges of contemporary science. Like many of his rabbinic colleagues, scientifically his horizons remained confined by a medieval worldview, his cosmology rooted in the Bible and the Talmud, with no hint of the dramatically expanding Copernican Universe.

Despite these lacunae, I hope to have succeeded in convincing readers of the many levels of importance in the manuscripts of Morteira’s sermons. First, they are uniquely abundant documents for the history of Jewish preaching, reflecting its homiletical and exegetical art at a consummate level. The canon of medieval and early modern Jewish preachers, as it had been established by the few scholars who investigated the field, consisted almost exclusively of individuals whose written legacy was limited to a single book of sermons (occasionally supplemented by exegetical works), analogous to Morteira’s Giv‘at taken from my article published in the Second Supplement to the Encyclopedia of Judaism (Leiden : E.J. Brill, 2004 Sha’ul, with one sermon for each Biblical lesson. The 550 manuscript sermons, a unique corpus for the period, enable us to evaluate a preacher’s productivity week after week for an entire career. Although he re-used some of his material, especially during the last two decades of his life, he continued to deliver carefully crafted and intellectually stimulating sermons for more than four decades. The quality of the printed sermons is not noticeably higher than that in the manuscripts; they were not selected because of their special brilliance, nor were they (with rare exceptions) extensively re-worked and polished for publication. The entire corpus of texts in manuscript and in print represents a consistently high level of creativity under the pressure of time, sustained by their author throughout much of his life.

In addition to their importance for the history of Jewish preaching, the sermons are windows into one of the most fascinating and dynamic Jewish communities of the early modern period. Abundant evidence about this Portuguese community, preserved in various archives and in the writings of some of its members, has been mined by scholars whose conclusions have appeared in a spate of recent articles and books. Until now, Morteira’s sermons remain the largest untapped body of primary source material for this community. Even if the information they provided pertained only to its leading rabbi, they would be valuable for this reason. But as I have shown above, they illuminate aspects of the community as well: in eulogies about some of its leading figures, in names of individuals designated for special honors or terms of office, in references to institutions and events and special occasions, in criticisms of behavior that the preacher denounced as incompatible with proper Jewish life. The other rabbis of the community during this period>Isaac Aboab da Fonseca, Menasseh ben Israel, David Pardo>preached regularly as well, perhaps as impressively as Morteira, but as no collections of their sermons have been preserved, Morteira’s texts become the more significant.

Finally, viewed as a whole, these texts represent a sophisticated articulation of many aspects of Jewish tradition and Jewish historical experience, presented to intelligent laymen engaged in the process of discovering the meaning of being Jewish. They are creations of a highly talented and respected seventeenth-century rabbi>not a profoundly original thinker, but an undeniably gifted communicator and interpreter of traditional texts. Imagine a typical new member of the community. Arriving from Portugal in 1620 with only the most rudimentary knowledge of Judaism and almost no comprehension of Hebrew, he sits in the congregation on the Sabbath morning trying to follow the service. As he gradually becomes more familiar with the prayer book, he still listens to the required Hebrew readings from the Pentateuch and Prophets without understanding what they meant beyond the lingering memories from a Christian education. For such a congregant, it is not far-fetched to conclude that the sermon delivered by a young rabbi in Portuguese, exploring one of the Biblical verses in conjunction with a passage from rabbinic literature and a conceptual religious problem, might well be one of the highlights of the morning. Furthermore, that the hypothetical listener not only would have been impressed by the clarity of the preacher’s presentation and the elegance of his delivery, but that he would also have learned something about that Biblical verse, or about the rabbinic text, or the problem that the preacher raised and explored, something that would remain with him.

As the weeks and years elapsed the listener would find himself, while becoming more familiar with the liturgy and the rituals, also accumulating a wealth of such insights and integrating them in his mind, so that new information acquired from the weekly pulpit discourse would begin to fit into a pattern. Occasionally, he would hear the vaguely troubling Christian arguments he remembered from his childhood education in Portugal rehearsed and rebutted. He would hear Jewish teachings about the tradition of Torah that the Christians had derided cogently defended. From time to time he would be informed that certain patterns of behavior, though familiar and perhaps even prevalent, were unacceptable to the rabbi and should be improved. Frequently he would be reminded that he and his family and friends were protagonists in a great drama of a noble people exiled from its land, buffeted by many nations, uprooted from newer homes, but destined for ultimate vindication. A drama of events that were the result neither of the vagaries of chance nor of the brutality of power politics, but were rather encoded in the Bible and remained under the direct providential supervision of the Master of the Universe. Gradually, through the ongoing educational program of the sermons, the listener might begin to feel comfortable in his new identity and in the tradition that, though new to him, was presented from the pulpit as something ancient, venerable, and precious. Through the sermons, alongside the other instruments of acculturation mobilized by the community, the “New Jew” would begin to feel rooted.

I conclude with a special plea. This source material should not remain unpublished, accessible only to those who visit the Library of the Rabbinical Seminary in Budapest or the Institute for Microfilmed Hebrew Manuscripts in Jerusalem. Many Hebrew texts of far less literary and historical significance are available in multi-volume printed editions. The entire corpus of Morteira’s manuscript sermons deserves to be published, in an edition that will identify texts cited by Morteira (Biblical verses, rabbinic passages, quotations from or allusions to medieval writers), note the cross-references to other sermons delivered earlier, include some discursive annotation where the content requires explanation for the non-specialist reader, and highlight points of comparisons with Morteira’s other works (especially the Tratado). A comprehensive cumulative index for the entire corpus will be invaluable.

This will not be a simple publishing task. While many of the sermons are fully legible from the microfilm to those who have mastered the author’s script, many others contain passages legible only from the original manuscripts. The task of transcription will be extremely demanding. Publication is too large a project for any one person; rather, a team of scholars with different areas of expertise would ideally cooperate. The finished project would be a monumental contribution to Jewish scholarship.

Those who are interested in the history of Jewish preaching look with envy at the splendid multi-volume annotated editions of sermons by such Christian preachers as John Donne, Jonathan Edwards, and John Wesley. Morteira’s homiletical oeuvre is worthy of a comparable treatment.

Earlier Published Studies of Saul Levi Morteira's Sermons

"The Sermon as Art-Form: Structure in Morteira's Giv'at Sha'ul," Prooftexts 3 (1982): 243-61 ("Your Voice Like a Ram's Horn," pp. 107-26).

"Saul Levi Morteira's Treatise on the Immortality of the Soul," Studia Rosenthaliana 25 (1991): 131-48.

"Saul Levi Morteira's Eulogy for Menasseh Ben Israel," in A Traditional Quest: Essays in Honour of Louis Jacobs, ed. Dan Cohn-Sherbock (Sheffield, 1991): 133-53 ("Your Voice Like a Ram's Horn," pp. 411-44, including Hebrew text).

"The Hesped as Historical Record and Art-Form: Saul Levi Morteira's Eulogies for Dr. David Farrar," ("Your Voice Like a Ram's Horn," pp. 367-410, including Hebrew text).

"History as Homiletics: The Use of Historical Memory in the Sermons of Saul Levi Morteira," in Jewish History and Jewish Memory: Essays in Honor of Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi, ed. Elisheva Carlebach, John M. Efron, and David Myers (Hanover, NH: Brandeis University Press, 1998), pp. 113-33.

"The Manuscript's of Morteira's Sermons," in "Studies in Jewish Manuscripts," ed. Joseph Dan and Klaus Herrmann" (Mohr Siebeck, 1999), pp. 171-98.

"The Sermon as Oral Performance," in Yaakov Elman and Israel Gershoni, editors, Transmitting Jewish Traditions: Orality, Textuality, and Cultural Diffusion (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000), pp. 248-78.

"The Rhetoric and Substance of Rebuke: Moral and Religious Authority in Morteira's Sermons," Studia Rosenthaliana 34 (2000): 131-152.

"Exile in Amsterdam: The Evidence in the Sermons of Saul Levi Morteira," in Me'ah She'arim: Studies in Medieval Jewish Spiritual Life in Memory of Isadore Twersky (Jerusalem: Magnes Press, 2001), pp. 209-249.

"Christianity, Christians, and 'New Christians' in the Sermons of Saul Levi Morteira," Hebrew Union College Annual 70-71 (1999-2000): 329-84.

Back to Top

Course Descriptions and Syllabi

Spring 2002 Courses

Honors 175: Jerusalem in History

Jerusalem's sacred status for Judaism, Christianity and Islam remains at the center of the competing claims to the city. It was the capital of a Jewish state under David, became an important Christian city under the late Roman and early Byzantine periods and was conquered by the Muslims in the seventh century. Except for a brief period under the Crusades, the city remained under Muslim rule until the early twentieth century. Beginning in 1948, it became the contested capital of the State of Israel. This course will explore the history of the city from Biblical times to the present with special emphasis on three themes: the changing meaning of the sacred geography of the city, the various ways that the city was ruled under different regimes, and the relations among the three religious communities residing in the city.

History 6660:

Jews in Late Medieval and Early Modern Christian Europe

(Revel Graduate School, Yeshiva University)

A study of Jewish historical experience during the transition from the Middle Ages to the early modern period (ending ca. 1650, before the outbreak of the Sabbatian movement). Following the reversals of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, the course will examine the dynamics of Jewish life in Portugal, Italy, Reformation Germany, Prague and Poland, Amsterdam and England. Emphasis will be on new trends in historiography (studies written in the past generation, and especially in the past decade, by American and Israeli scholars).

History 5350: The Sermon as Art Form and Historical Resource

(Revel Graduate School, Yeshiva University)

This course is intended to introduce students to the investigation of medieval, early modern, and modern Jewish sermons through a close reading of selected texts. Methodological problems, such as the relationship between the extant written record of the sermon and the oral communication, will be addressed. Our goal is to cultivate an appreciation of the sermon both as a genre of Jewish literature and as a resource for understanding the rabbi and his congregation within a specific historical setting.

Spring 2003 Courses

History 114: History of the Jews in Islamic Lands

Major themes: the legal status of Jews under Islam; the impact of the Muslim conquest and Abbasid rule upon the Jewish community of Babylonia; the flourishing Jewish civilization in Muslim Spain; Mediterranean Jewish society in the High Middle Ages; Jewish life in Ottoman Turkey.

Fall 2003 Courses

History 113: History of the Jews in Christian Europe to the 18th Century

Examines the position of the Jews in relation to church and state; traditional Jewish society and self-government of the Jewish community; movements of Jewish spirituality in their cultural contexts (philosophy, mysticism, German and Polish Hasidism); changing population centers; the background of emancipation and enlightenment.

History 161: Jewish Historical Writing

A survey of Jewish attitudes toward history and examples of Jewish historiography beginning with the Hebrew Bible. Emphasis will be placed on medieval and Renaissance historians, and on the flourishing of historical writing in the past 150 years in Europe, in Israel, and in the United States.

Spring 2004 Courses

Analyzes the origins, causes and significance of the Nazi attempt to destroy European Jewry, within the context of European and Jewish history. Related themes: the behavior of persecutors, victims, and bystanders; literary responses; contemporary implications of the Holocaust for religion and politics. Prior course in Jewish/European history recommended.

An analysis of articulated hatred toward Jews as a historical force. After treating precursors in the pagan world of antiquity and in classical Christian doctrine, the course will focus on the modern phenomenon crystallizing in 19th-century Europe and reaching its lethal extreme in Nazi ideology, propaganda, and policy. Expressions in the U.S. and in the Arab world, as well as Jewish reactions to anti-Semitism, will also be studied.

Summer 2004 Courses

History 158: Modern Jewish History

A survey of major events and trends in the history of the Jewish people from the eighteenth century to 1948. Central themes include the impact of Enlightenment and the struggle for Emancipation, new religious expressions of Judaism, modern antisemitism and the Holocaust, Zionism, and the American experience. Focus will be on the analysis of primary sources.

Back to Top

Fall 2004 Courses

History 114: History of the Jews in Islamic Lands

Major themes: the legal status of Jews under Islam; the impact of the Muslim conquest and Abbasid rule upon the Jewish community of Babylonia; the flourishing Jewish civilization in Muslim Spain; Mediterranean Jewish society in the High Middle Ages; Jewish life in Ottoman Turkey.

History 115: Messianic Movements and Ideas in Jewish History

Survey of messianism as a central force in Jewish history, stressing both theoretical implications and concrete manifestations. Topics: biblical messianism, the rise of Christianity, medieval speculation, the Sabbatian movement, Zionism.

Back to Top

Fall 2005 Courses

History 113: History of the Jews in Christian Europe to the Eighteenth century

Examines the position of the Jews in relation to church and state; traditional Jewish society and self-government of the Jewish community; movements of Jewish spirituality in their cultural contexts (philosophy, mysticism, German and Polish Hasidism); changing population centers; the background of emancipation and enlightenment.

A study of the history, literature, thought and spirituality of Hasidism from its beginnings in the 18th century to the present. The relationship between Hasidism and other movements in modern Jewish history (Talmudism, Haskalah, Zionism) will be explored.

Back to Top

Spring 2006 Courses

History 158: Modern Jewish History

A survey of major events and trends in the history of the Jewish people from the eighteenth century to 1948. Central themes include the impact of Enlightenment and the struggle for Emancipation, new religious expressions of Judaism, modern antisemitism and the Holocaust, Zionism, and the American experience. Focus will be on the analysis of primary sources.

History 159: The Holocaust

Analyzes the origins, causes, and significance of the Nazi attempt to destroy European Jewry, within the context of European and Jewish history. Related themes: the behavior of persecutors, victims, and bystanders; literary responses; contemporary implications of the Holocaust for religion and politics. Prior course in Jewish or European history recommended.

Back to Top

Current Research

Since the completion of my book on the sermons of Saul Levi Morteira in seventeenth-century Amsterdam, I have been following the genre in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. This new chronological interest has been a spin-off from my work on Witness from the Pulpit. Having discovered powerful and poignant sermons delivered by my father in response to Nazism and the news of the growing destruction of European Jews, I decided to read more widely on what rabbis were saying from their pulpits between 1933 and 1945, a subject that has never been investigated previously. My paper at the World Congress of Jewish Studies in August 2001 was based on sermons from the High Holy Days of 1939-1943 as each year the news from Europe worsened.

I have recently finished a manuscript for a new book, to be called Ploughshares Into Swords: American- and Anglo-Jewish Preaching in Times of War, 1800-2001, which is currently under review for publication. Click here to read my preliminary general survey of "changes in the modern sermon" taken from my article published in the Second Supplement to the Encyclopedia of Judaism (Leiden : E.J. Brill, 2004), pp. 2265-2283; an expanded version will serve as the general introduction to the new book. This will be followed by some 35 sermon texts, most of them not known even to most scholars, with individual introductions and full annotation illustrating their historical significance.

A second project in which I am currently engaged is the preparation, together with my colleague Prof. Nancy Berg of Washington University in St. Louis, of an anthology of texts on “Exile in Jewish Historical Experience and Literary Expression.” This derived from an interdisciplinary course that we co-taught in 1996. Our goal is to produce a reader of primary texts from all periods of Jewish history and all genres of Jewish literature that will illuminate the various aspects and ambiguities of Exile. Click here to read the introduction to a co-authored article on this topic published in the Association for Jewish Studies Review, 26:2 (2002): 301-26.

Back to Top